MAP-Elites is an elegant algorithm for solving general optimization problems. To be more accurate, it is an illumination algorithm that tries to find high-performing and diverse solutions in a search space. At its core, it is a simple algorithm, both conceptually and to implement. Here, I briefly introduce the main idea behind the algorithm and its components. I will also discuss its merits and demerits compared to other approaches. This note is based on Illuminating Search Spaces by Mapping Elites.

Also checkout my notebook (GitHub or Colab) for an implementation on a toy example and some cool visualizations!

Algorithm

Let’s say we have a search space $\mathcal{X}$ within which we want to find a desirable solution. First, we need to have a function $f:\mathcal{X}\to\R$ over this search space that gives a performance score to each solution. In traditional optimization terms, this is the objective function that is to be maximized. Second, we need to select $N$ dimensions of variations that define a feature space, $\mathcal{B}\subseteq \R^N$. Each point in the search space is mapped into this feature (or behavior) space via a behavior function $b: \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{B}$. Notice that this behavior space typically has less dimensions compared to the original search space.

To give a concrete example, let’s say we want to find a policy for a robot so that it can finish a race in the fastest time possible. Here, the search space is the space of all possible policies. If a policy has $n$ parameters, then $\mathcal{X} = \R^n$. The performance measure, $f$, is the time it takes for the robot to finish the race. We might use different features to create the behavior space, $\mathcal B$. For instance, we may use the length of its steps, how frequently it jumps, its energy consumption, etc. This way we can define the behavior $b(x)$ for any policy $x \in \mathcal{X}$. Again, note that whereas our search space $\mathcal{X}$ can be high-dimensional, the behavior space can have as few as one or two dimensions.

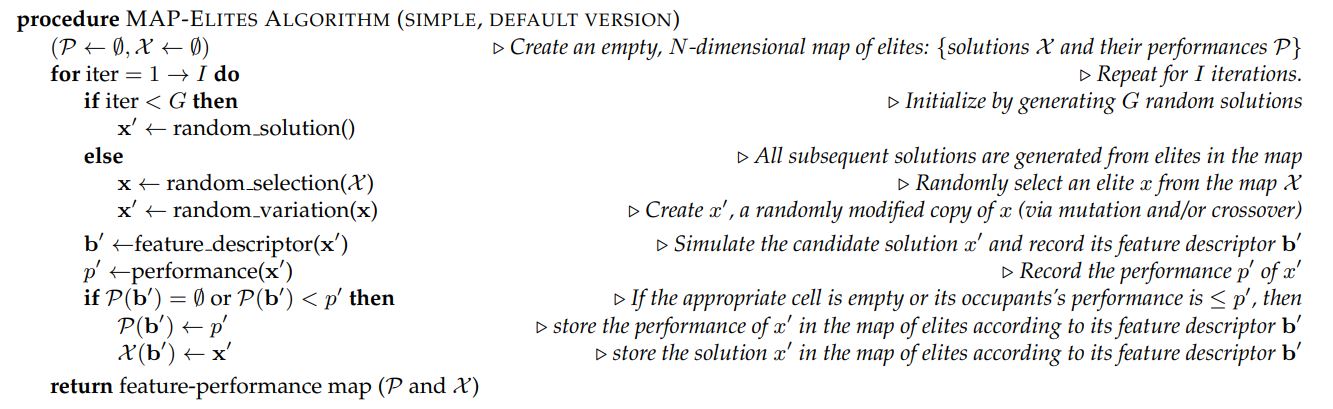

In MAP-Elites each dimension of variation in the behavior space is discretized and the behavior space is turned into a grid. We will then generate $G$ initial points and determining their performances and behaviors. Each of these points are put into the grid cell (in the behavior space) that they belong. In case multiple points are assigned to the same cell (i.e., have similar behaviors), only the one with the highest performance is kept. These points constitute the initial elite population. After this initial random generation, at each step we randomly select one of the elites and mutate it to get a new point. This mutation can be as simple as adding some random noise, or some other complicated operation like cross-over (which uses multiple elites), gradient-based optimization, etc. The performance and behavior of this new point are evaluated and the generated point is kept if it is an elite (i.e., has the highest performance in its corresponding cell in the behavior grid).

Below is the general backbone of the MAP-Elites algorithm, taken from Illuminating search spaces by mapping elites, Jean-Baptiste Mouret and Jeff Clune, 2015.

Discussion

Flexibility

One important feature of the MAP-Elites is how flexible the algorithm is. Some of the things that we can tweak include

- Discretization: The granularity of the discretization is something that we control, based on the resources that are available. It could even be dynamic, we may want to gradually merge the cells so that in the end we are left with one solution that has the best performance.

- Mutation: Following the traditional mutations in evolutionary optimization literature, vanilla MAP-Elites mutates the solutions by adding random noise to them. We could imagine other strategies for generating new solutions from the current set of elites. For instance, we could perform a cross-over operation over a number of the solutions, or perform several gradient ascent steps (when the objective is differentiable).

- Behavior Space: The features that form the behavior space need not be hand-crafted. It may be possible to explicitly tune the behavior space and the feature descriptor function $b$ as the algorithm progresses.

MAP-Elites vs. Optimization

Contrary to most ordinary optimization algorithms, MAP-Elites maintains a population of solutions. So, naturally, we need more memory to store the solutions (just imagine storing a large population of neural-nets with millions of parameters!). Why would we do that? What are some of the advantages that an illumination algorithm can bring to the table that might justify this additional computational overhead? To answer this question, we investigate several criteria that are used to evaluate optimization and illumination algorithms.

- Global Performance: The most basic criterion for evaluating the performance of any optimization algorithm is to measure the quality of the best solution found. Pure optimization algorithms generally yield better performing final results, which is expected as they are solely focused on maximizing $f$. However, in practice, MAP-Elites can find very good performing solutions and be competitive with traditional optimization algorithms. Because in MAP-Elites a larger portion of the search space is covered, the chances of stumbling upon a high-performing region in the search space gets higher.

- Reliability: If we average the highest performing solution found for each cell in the behavior grid, across all runs and divide it by the best known performance in that cell, we get a measure of how reliable the algorithm is at finding good solutions with a particular behavior. This is an important performance measures for an illumination algorithm, as it indicates how clear is the picture of the behavior space that the algorithm gives us. Traditional optimization algorithms usually find high-performing solution but at the expense of coverage.

- Coverage: The average number of cells in the behavior grid that a run of the algorithm is able to fill. Optimization algorithms usually perform much worse than illumination algorithms in this regard.

Now, let’s see why we might want to encourage diversity. After all, the ultimate goal of optimization is to find a single highest-performing solution. There are several reasons why having a population of elites may be more desirable, albeit at the cost of consuming more memory.

- Robustness and Adaptation: When we have multiple good-enough solutions, each with different behaviors, we can get an ensemble of solutions that is much more robust to changes. Consider the racing robot example. If the racing environment suddenly becomes a bit more slippery, then the one high-performing solution may suddenly become completely obsolete. Whereas some other solution may now become optimal. Generally speaking, having multiple ways of solving a problem, gives us more ability to adapt when the environment changes.

- Better Coverage $\rightarrow$ Better Optimization: MAP-Elites encourages exploration in different parts of the behavior space. This in itself could lead to finding high-performing regions in the search space. In the contrary, if an optimization algorithm starts out in a low-performing region, it is highly unlikely that it ever breaks free and explores other regions. This issue of getting stuck in local optima is something that all gradient-based optimization methods struggle with.

- Performance-Behavior Relation: MAP-Elites illuminates the fitness potential of the whole behavior space, and not just the high-performing areas. This can potentially reveal relations between the performance and the dimensions of interest in the behavior space.

- Diversity!: Finally, MAP-Elites allows us to create diversity in the dimensions of behavior that were chosen.